It’s taking me forever to unpack from my last trip to Montana. I’m recovering from the fourth trip in a year following bison, North America’s largest mammal. I run one more load of wash, bundle up tent cord, sort bins and stuff sacks, and clean camera gear. I struggle through re-entry again, obsessively returning to my computer morning and night to work on this story map project, tracing the trail of bison from past to present.

And a voice in the back of my distracted head asks why this is happening again.

Part of the problem lies with me. I finally confessed in a recent presentation to a fundamental characteristic and character flaw. Something out of pattern catches my eye, and if it piques my curiosity, I follow it, getting caught up sometimes for years. This behavior can lead either to enlightenment or to despair, if you think about it.

My neighbor from the Conservation District got me signed up for the annual bareroot plant sale 14 years ago (maybe 15). I was hooked when my red flowering currant became a beacon for hummingbirds. A sort of mad scientist/greedy gardener took over and I spent years buying and propagating thousands of plants to get more wildlife. I became a Native Plant Steward, and volunteered to give workshops and classes to thousands of people. I blogged about my backyard wildlife, gave away plants, took thousands of photos, started making videos.

Blame this chapter on the stoic and infinite bison, and the human history they drag behind them like clattering cans tied to a wedding limousine. Only this wedding, it turns out, is an arranged marriage where the bison might need a divorce from an abusive spouse.

I planned my first trip to Yellowstone National Park to explore America’s oldest national park and to see grizzly bears. I did my homework to stay out of trouble around wildlife. When a large herd with agitated bulls spread across Mary Mountain Trail, we high-sided the slope, skirting through the woods where grizzlies might lurk. The grizzlies seemed lower risk compared to the snorting, pawing bulls. Whenever we arrived at a new campsite, we waited out the customary giant bull resting in the shade.

The last backpack trip journeyed into Slough Creek Valley. I was comfortable enough around bison to bail out two New York fly fishermen who got pinned on top of their bear box when a big herd took over their camp. One evening, I sat eating dinner on a hill overlooking the valley watching a big herd flow slowly through the valley. The low rumble rolling across the herd and through the valley reminded me of some National Geographic image showing herd migrations in Africa or the Arctic.

Of course, Yellowstone treats visitors to a perspective on co-managing large wildlife and people. I came away realizing how disconnected most of us are from nature: we view the outdoors as a zoo, a playground, and a fitness trail. I realized how poorly wildlife mixes with roads and cars and our impatience with anything that creates traffic disruption.

During a wolf workshop at Lamar Buffalo Ranch the next spring, it became apparent that bison tolerate us but don’t need us. A lone bison bull hung around the ranch, resting on the shoveled paths and scratching his rear on the cabin railing. He seemed to be taking advantage of what we build, but it didn’t mean he and his brethren need us. On a field trip, I watched through a spotting scope as a bull hobbling on a broken leg stood up to a hungry pack of wolves. Surprisingly, they backed down from the injured bison and ambushed an elk instead. That’s tough.

Then I wandered onto American Prairie Reserve, where the future vision is as expansive as the prairie horizon. APR envisions a 3-million acre fabric of private/public lands for bison, other wildlife, and people to roam free. The bison were boss in the unit I visited. There were no bison jams. I could wander across grasslands on all-encompassing treasure hunts to see rocks, fossils, and flowers. The skies were big, uncrowded. I found peace.

Then I wandered onto American Prairie Reserve, where the future vision is as expansive as the prairie horizon. APR envisions a 3-million acre fabric of private/public lands for bison, other wildlife, and people to roam free. The bison were boss in the unit I visited. There were no bison jams. I could wander across grasslands on all-encompassing treasure hunts to see rocks, fossils, and flowers. The skies were big, uncrowded. I found peace.

I happily spend most of my free time alone, but I like to communicate. So I wanted to tell about this place, put bison in a natural conext and beckon people to the ocean of grasslands they are missing. A simple story, right?

And then I stumbled on the winding and overgrown trail into bison history. See, I bought into the Yellowstone narrative of a few years ago. The U.S. government saved the remaining 25 bison after twenty years of intense and deliberate extermination. The army helped save them from poachers and founded the National Park Service. Today, they’re doing just fine- almost half a million on the ground.

Then I found out most bison are in commercial herds, and they have leftover cattle genes. Over a century after the slaughter ended, there are only an estimated 8,000 pure bison in the wild.

And there isn’t just one heroic bison savior story rooted in the right intentions. Profiteering played a role. Then I found out how three men with native blood and the Canadian government triggered the establishment of public herds in the United States. I followed the Pablo-Allard herd to Elk Island National Park in Alberta, but found no Hallmark Holiday Special ending for these animals. Those animals, along with elk and moose, were destined for long-gone Buffalo National Park. When they overran the park, animals were shipped to Wood Bison National Park. Cross-breeding with their cousins and disease almost doomed wood bison to extinction. Buffalo Park failed after 31 years. The Department of Defence took over the property and today keeps a small herd in memory of the past.

The Canadian government learned lessons from the past, but has the U.S.? Elk Island National Park has taken public comment on alternatives to keep bison, moose and elk at healthy numbers. Meanwhile, America’s National Bison Range is described in a Missoulian article as “popular, poor, and rudderless”.

And those stories just keep surfacing.

Along the way I came across buffalo jumps, the most spectacular form of communal hunting practiced by Plains Indians. I stood at jumps and imagined tension followed by the breathtaking explosion of a stampede. I touched shards of ancient, splintered bone eroding from the old blood kettles at First Peoples Buffalo Jump. I followed the trail to Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. I read Jack Brink’s vibrant book about Plains Indians, communal hunting and this special site.

I discovered the tsunami effect of western expansion across North American, and how hubris and profiteering triggered the near extinction of bison. The perspective is chilling given the federal government’s current drive to go back in time.

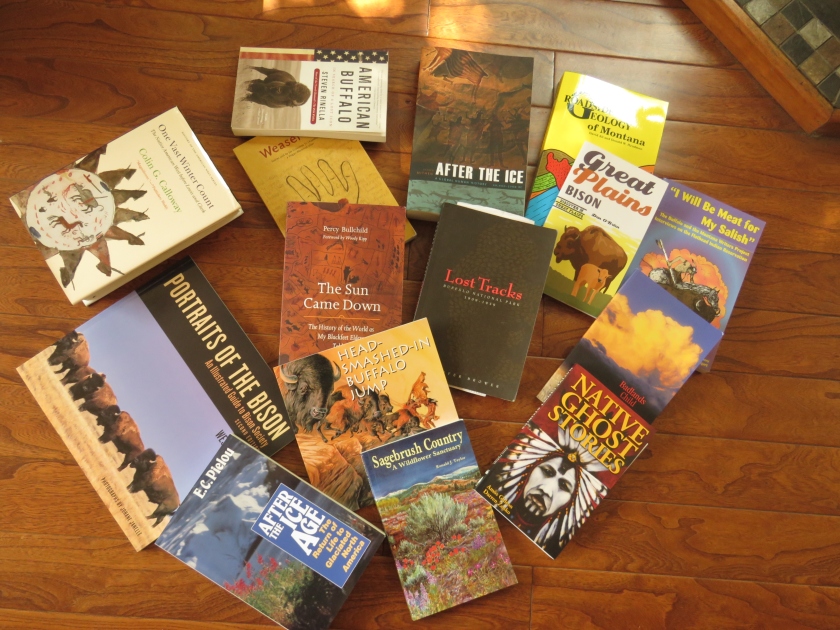

My bedside table is stacked with books and papers. Some chronicle history and others propose strategies to preserve truly wild bison into the future.

Bison don’t need us; they can take care of themselves. They just need land to grow and roam, and water. Aside from a few large herds, there are 80 bison here, 100 there. Wild bison survival depends on big herds in big places, shaping the land and being shaped by nature.

Bison may not need people, but we still need wild bison and wild places. We need them to remind us there are healthier, more viable alternatives to an urban life dominated by the technology explosion. We’re careening blindly toward a future of self-driving cars, artificial intelligence, and chat bots managing us via social media. We need to remember we’re not that far from our roots, that we are still governed by nature. We need bison to teach us some history lessons so we don’t repeat the worst of the past. We need them to school us in patience and give us peace.

Bison may not need people, but we still need wild bison and wild places. We need them to remind us there are healthier, more viable alternatives to an urban life dominated by the technology explosion. We’re careening blindly toward a future of self-driving cars, artificial intelligence, and chat bots managing us via social media. We need to remember we’re not that far from our roots, that we are still governed by nature. We need bison to teach us some history lessons so we don’t repeat the worst of the past. We need them to school us in patience and give us peace.

And while I need to come up for air and take care of everyday things, I really need to get this story out. It’s haunting me now.

Plains Indian tribes followed these animals across North America, leaving their own trail, including camps, kill sites, and ritual locations. My first visit to a buffalo jump led to places where I could understand communal hunting, from Madison Buffalo Jump to the superb Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. This World Heritage site is the best preserved in the world with a phenomenal interpretive center.

Plains Indian tribes followed these animals across North America, leaving their own trail, including camps, kill sites, and ritual locations. My first visit to a buffalo jump led to places where I could understand communal hunting, from Madison Buffalo Jump to the superb Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. This World Heritage site is the best preserved in the world with a phenomenal interpretive center.

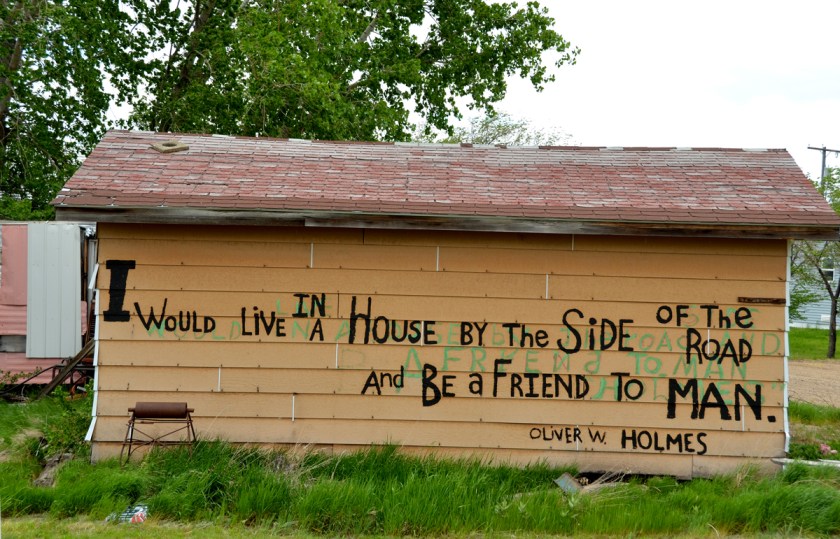

Remember when you first felt freedom? Whether freedom is frightening or thrilling, people usually have a “first freedom” story. We realized we get to make choices about our lives, vote, leave on a plane by ourselves for the first time, walk through the door on our own apartment or house.

Remember when you first felt freedom? Whether freedom is frightening or thrilling, people usually have a “first freedom” story. We realized we get to make choices about our lives, vote, leave on a plane by ourselves for the first time, walk through the door on our own apartment or house.

Somehow I missed that stage in adulthood where people decide camping is too hard, and either stay in motels or travel in trailers with a compact semblance of home. I hit motels on long driving days, or when I need a shower and a real meal.

Somehow I missed that stage in adulthood where people decide camping is too hard, and either stay in motels or travel in trailers with a compact semblance of home. I hit motels on long driving days, or when I need a shower and a real meal.

Disasters aren’t disasters without images of people’s damaged belongings. After a flood, our screens scroll images of drowned livestock, crushed barns, mangled cars, crumpled roads and bridges. Earthquakes shear highways and splinter houses into junk piles with people trapped underneath. The awful feeling wouldn’t be there without us; it would just be an event.

Disasters aren’t disasters without images of people’s damaged belongings. After a flood, our screens scroll images of drowned livestock, crushed barns, mangled cars, crumpled roads and bridges. Earthquakes shear highways and splinter houses into junk piles with people trapped underneath. The awful feeling wouldn’t be there without us; it would just be an event. The speeding automobile smears the landscape into a monotonous panorama stretching for hours. We grow stiff from sitting and it seems endless. But speed did not create this impression of the prairie. Even settlers who rumbled along in wagons or on foot didn’t see the complexity of the landscape. There seem to be more books about hard life than prairie songs on the shelves.

The speeding automobile smears the landscape into a monotonous panorama stretching for hours. We grow stiff from sitting and it seems endless. But speed did not create this impression of the prairie. Even settlers who rumbled along in wagons or on foot didn’t see the complexity of the landscape. There seem to be more books about hard life than prairie songs on the shelves. Innocence is the culprit, aided by fear. Powered by animal or fuel, we travel the prairie as if in a foreign land. It looks different from our homes. The sky looms larger, with a hundred-mile view of circling weather and no hint what it means to us. Cacti lurk on the ground and rattlesnakes in the sage. The prairie has a different rhythm that enchants the curious or unnerves the timid.

Innocence is the culprit, aided by fear. Powered by animal or fuel, we travel the prairie as if in a foreign land. It looks different from our homes. The sky looms larger, with a hundred-mile view of circling weather and no hint what it means to us. Cacti lurk on the ground and rattlesnakes in the sage. The prairie has a different rhythm that enchants the curious or unnerves the timid. Each journey to dry country fills my eyes with the richness of seemingly barren land. This trip is my first as an artist to

Each journey to dry country fills my eyes with the richness of seemingly barren land. This trip is my first as an artist to

My car also displayed the damage of regular life.

My car also displayed the damage of regular life.

In the end, he wished me a good vacation and I continued my journey to Buffalo Camp. I set up my tent and sat down for dinner, watching the sun set over rich barrens ripe for exploration.

In the end, he wished me a good vacation and I continued my journey to Buffalo Camp. I set up my tent and sat down for dinner, watching the sun set over rich barrens ripe for exploration.

On my trek to the jump, I found butterflies, prairie dogs, and of course, bison. I flushed upland birds (probably grouse), took pictures of tracks and scat, and put one foot in front of the other, mile after mile.

On my trek to the jump, I found butterflies, prairie dogs, and of course, bison. I flushed upland birds (probably grouse), took pictures of tracks and scat, and put one foot in front of the other, mile after mile.

When you live in the inner city of a massive city and your family is poor, the schoolroom is a place that will make or break your future. You have no more access to services and benefits of the developed world than a ranch kid living 100 miles from a town. You have no wealth, power or authority behind you. Your only hope for any kind of future is to get a good education and move upward and out.

When you live in the inner city of a massive city and your family is poor, the schoolroom is a place that will make or break your future. You have no more access to services and benefits of the developed world than a ranch kid living 100 miles from a town. You have no wealth, power or authority behind you. Your only hope for any kind of future is to get a good education and move upward and out.

After speeding away to a special assignment that includes social media, my life and my blog have been left in a dust cloud, pressed flat in the gravel like dehydrated roadkill. I worked my old job and my new job for five weeks until my work got transferred. Days never really ended. I forgot things. I needed everything to slow down. I needed a break.

After speeding away to a special assignment that includes social media, my life and my blog have been left in a dust cloud, pressed flat in the gravel like dehydrated roadkill. I worked my old job and my new job for five weeks until my work got transferred. Days never really ended. I forgot things. I needed everything to slow down. I needed a break.

Finally, after setting up my temporary abode, I could stretch my legs walking out to the prairie dog town across the creek. I could watch the prairie sunset and moonrise and curl up well-insulated in my sleeping bag, ready to start exploring the next day.

Finally, after setting up my temporary abode, I could stretch my legs walking out to the prairie dog town across the creek. I could watch the prairie sunset and moonrise and curl up well-insulated in my sleeping bag, ready to start exploring the next day.