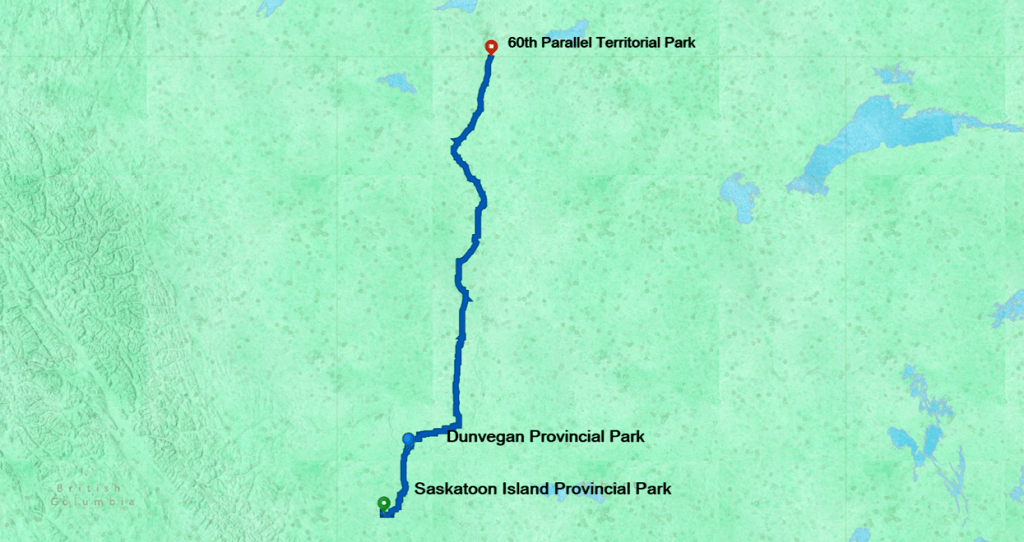

Monday dawned clear, an invitation to explore. The sun rose on a chilly and serene morning as I walked the shores of Great Slave Lake. After a late night watching the aurora, rolling out of a warm sleeping bag to catch the sunrise seemed like a stretch. But I had planned a day following water. Strolling the beach by the campground with a cup of coffee and a camera seemed like a good start.

You have to stand on the shores of the Great Slave to feel its draw. North America’s deepest lake stretches across the horizon like the ocean, and back in time to the last ice age.

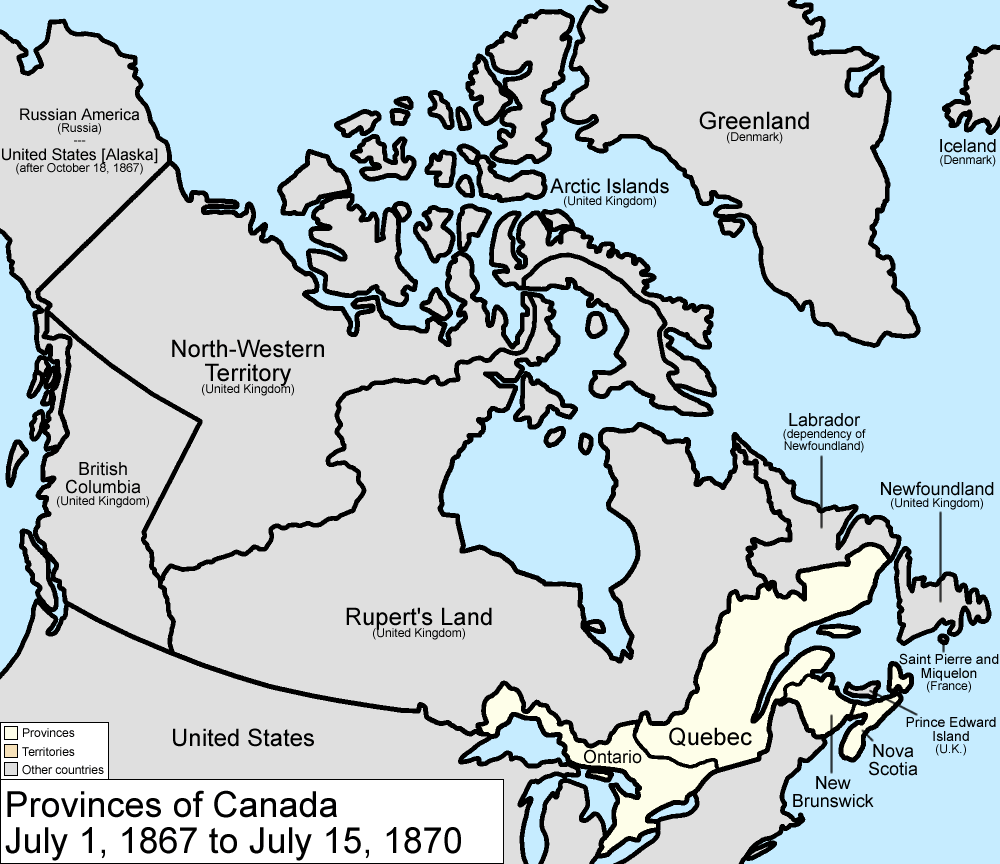

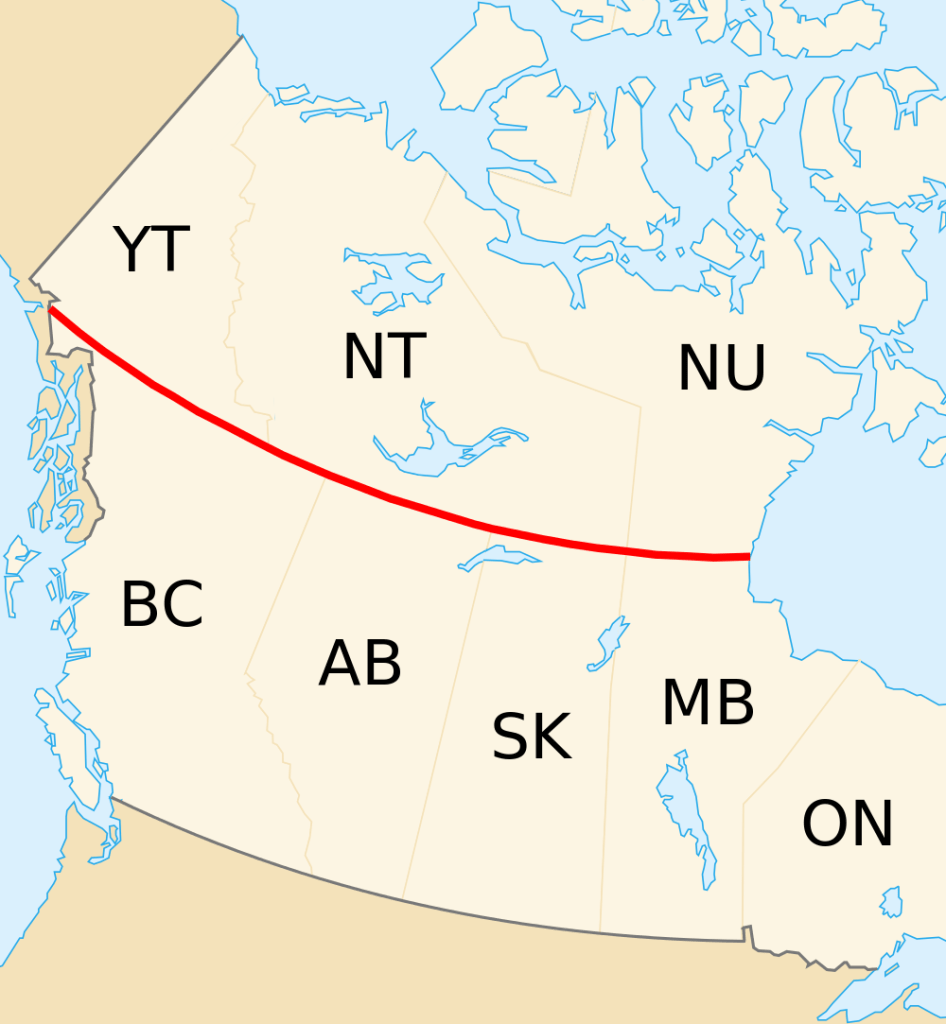

An arc of lakes from Great Bear Lake to the Great Lakes tells the story of the Ice Age that started about 2.5 million years ago and ended only recently. The Laurentide Ice Sheet covered northeastern North America, millions of square miles (or kms) shaping the landscape. The Laurentide butted up against the “smaller” Cordilleran Ice Sheet that covered almost a million square miles in the west.

In the last glacial maximum, from about 95,000-20,000 years ago, the Laurentide Ice Sheet scraped the basins of North America’s various Great Lakes, including the Slave.

The western boundary is marked by a change in geology even today. The Ice Sheet scraped away the surface to some of the oldest known rocks on the earth’s surface, shown in shades of orange and red below (along the line that cuts the Great Slave Lake in two, if you are color vision-impaired).

Those surfaces include stromatolites from about Precambrian times 2.5 billion years ago. Stromatolites are rare, appearing in Western Australia and as fossils in a few other places, including Northwest Territories. They are evidence of the beginnings of life, rock-like mounds built by lime-secreting cyanobacteria and trapped sediment. If you are not appropriately grateful, know that cyanobacteria were the first organisms to create an atmosphere rich enough in oxygen to support life as we know it.

The Hay River Visitor Centre has a display of stromatolites that I will examine more closely on my return visit next year. This time, I barely registered that I stood on the floor of ancient tropical seas, transported back to Deep Time.

Lands west of Great Slave Lake feature relatively younger rock than Archean lands to the east. In exposed areas, the western surface is a modest 358-419 million years-ish, the remains of the Devonian period. This area is shown in blue on the geologic map above.

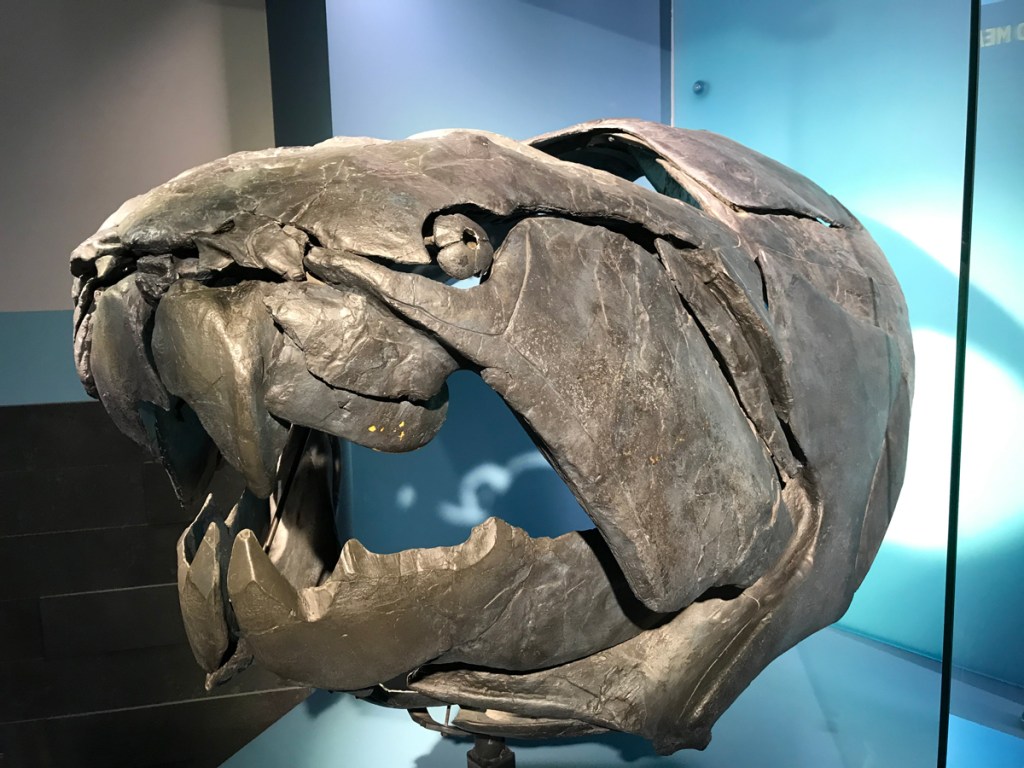

We call the Devonian period the Age of Fishes, when water covered the planet and complex reefs hosted diverse and sometimes monstrous-looking leviathans.

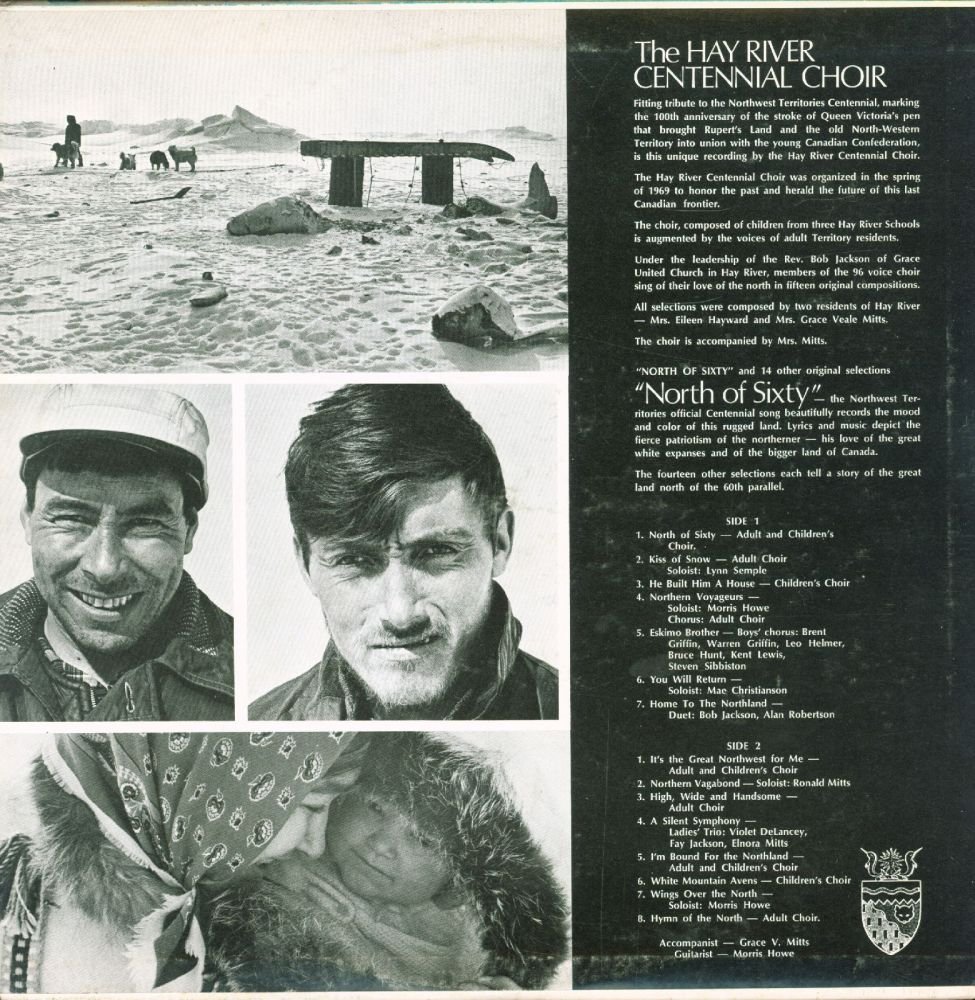

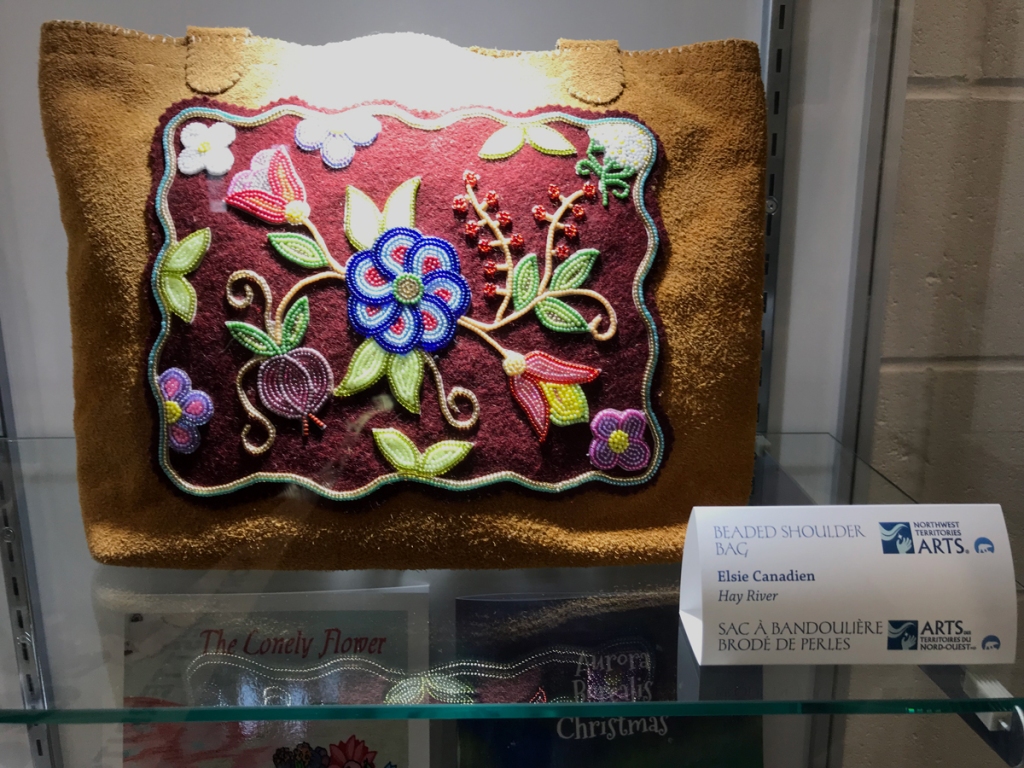

I would discover evidence of other ancient fish at the Hay River Visitor Centre. The Visitor Centre is open during the week in off-season, so I had to skip it when I arrived on a Saturday. I’m going to tell you to plan your trip to arrive there first. You need to get local travel tips, history, and environmental issues from Peter Magill. You should peruse the exhibits and local artisan work for sale.

When a large family from Yellowknife came in to the Centre, I turned away from brochures and gifts to investigate exhibits. I discovered that the waterfall route I had visited on my Sunday drive held a giant secret.

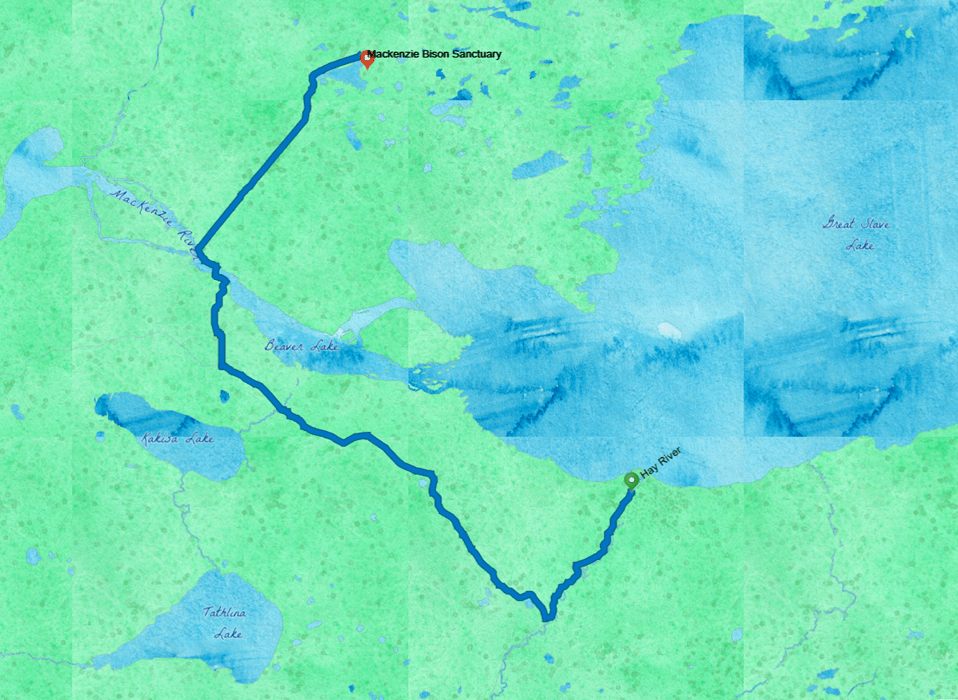

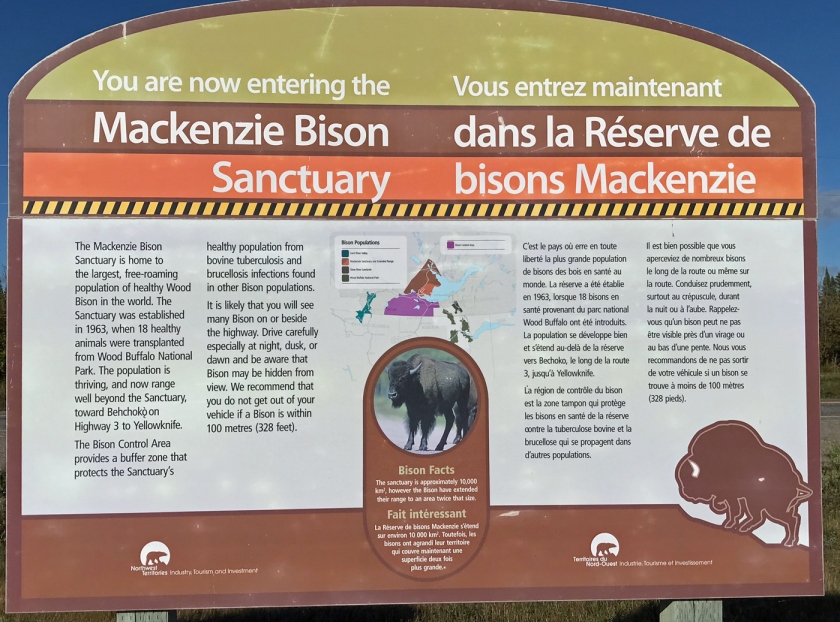

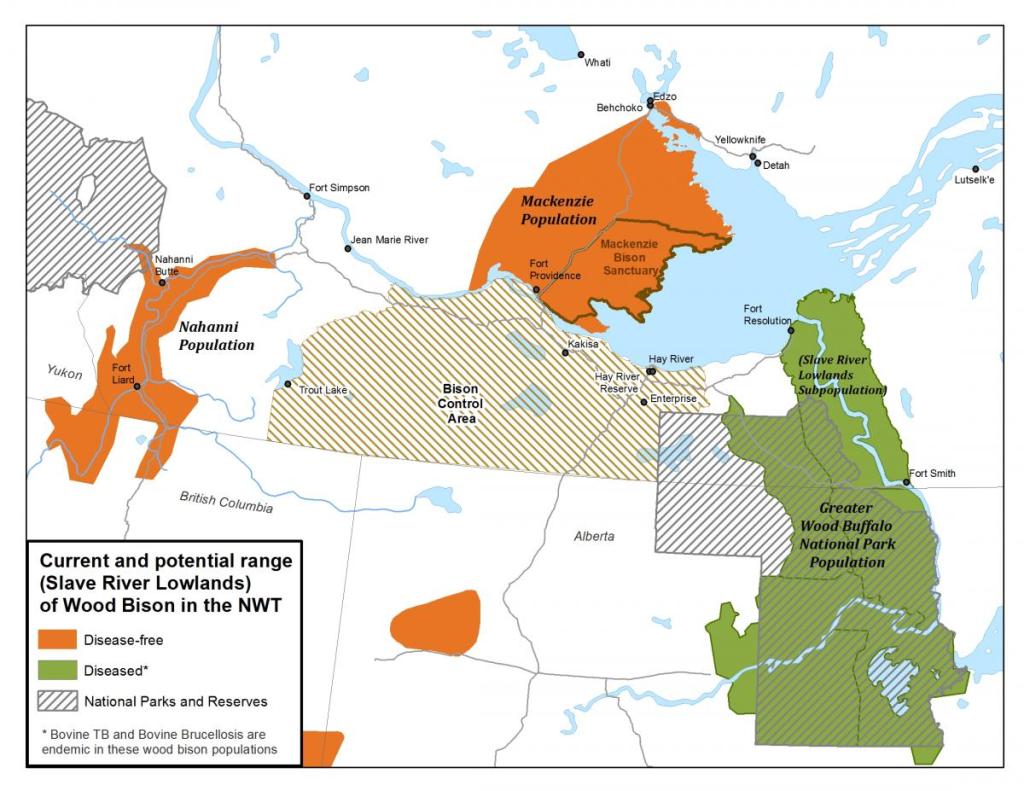

Full disclosure: I stopped at the waterfalls on the route to Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary because they are a tourist attraction. I am not one of those people who finds spiritual serenity in falling water. Instead, I sit at waterfalls contemplating natural history, geological forces and hydraulics. I find them fascinating as a force of nature, not of spirit. I know that peoples from time immemorial see and hear more than I can. I’ve given up on the divine where waterfalls are concerned.

The waterfalls are well worth your visit no matter what you see in them. In mid-September, I had them to myself. Perhaps because I wasn’t feeling well, I enjoyed just sitting in the warm sun and watching water flow over rock shelves sculpted by ancient ice. Lady Evelyn Falls was perhaps the loveliest of the three with a gentle arc sweeping from bank to bank. Alexandra was the most dramatic. Louise Falls featured the most interesting formation, a shelf of blocks.

What I missed during my Sunday waterfall drop-ins were fossilized trackways from Sarcopterygians, the first fish to set lobed fin on land.

Casts of individual tracks sit on the floor. I knelt down and felt them with my fingertips. I imagined a massive lobe-finned fish, the first tetrapod, hauling its huge body from a drying pool and moving slowly across the land to find more water.

Of course, I had to go and see the trackway. I now felt well enough to make the hike between Alexandra and Louise Falls. I could make it a day. I had food for lunch in the car. After talking with Peter awhile and buying local gifts for friends, I headed out.

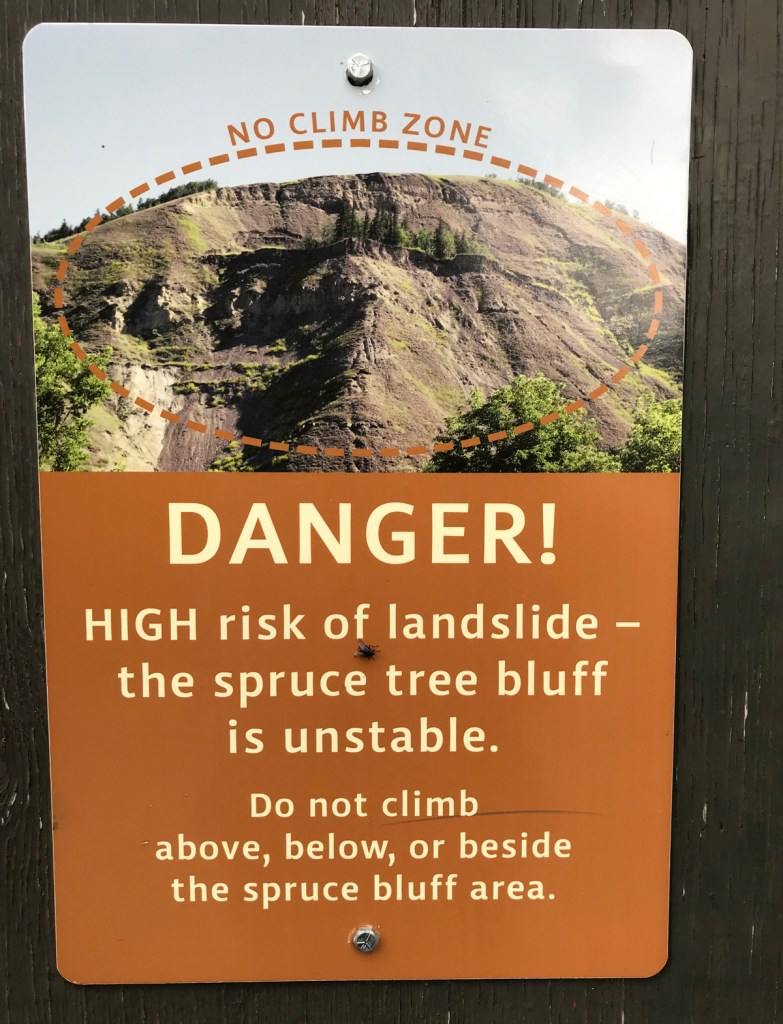

Alexandra Falls is easy to reach from the road. There is a parking lot I walked the trail to the river, but instead of turning downstream to the falls, I walked upstream. The bank and trackways erode every spring with battering by the Hay River. But the tracks from the display are still there. Further upstream I found more tracks, and fossil shells embedded in limestone.

I brushed fine debris from the depressions as I sat by the finprints drinking water-primordial, life-giving water. Water that beckoned fish to grow primordial hands and crawl onto the land.

I sat in the sun struggling to comprehend time. I always think of North America’s West Coast as young compared to the East, where old homes are a century older than my area. This all looks adolescent compared to parts of Europe, where crumbling stone tells of life a thousand years back. But this is age as measured by human occupation, not real time.

The rock I sat on bore traces of fish that lived almost 400 million years ago. I felt like dust- or the dust mites that appear only under electron microscope. We are really nothing in the face of Deep Time. A throwaway moment in the history of life. We seem so large and loud and destructive- but we are meaningless and small on a geologic scale.

We are, in fact, a chimera of ancient life. I sat there with my mess of flawed DNA that includes junk sequences from earlier beings and ghosts left behind by viruses. My body hosts microscopic flora, early life forms. Friendly flora help me digest my food and protect me from pathogens. Animal studies say that I would die in a sterile environment.

I sat in the thin fall sunlight with my hands resting in those fossil tracks and simply dissolved. What it meant to be human, to be me, vanished in colored droplets rising with the mist from the falls.

This realization might frighten or depress some people. I was glad I didn’t have a travel companion at that point.

Personally, I found this liberating. Soothing. All those to-dos and must-dos, the fears and hurt and failures. All the small successes that seemed so hard won. The looming questions about becoming an old person with an irritable immune system in a country threatening to cancel health care.

Nothing mattered, not really. Not in Earth’s impassive regard. The sheer act of being alive and touching deep time at that moment was more than a miracle. I could live in this precious moment experiencing dissolution and absolution. I could relax.

There are living Sarcopterygians, remnants of Deep Time still swimming in today’s oceans. The coelacanth, a Lazarus fish thought to be extinct 66 million years ago, was rediscovered off the east coast of South Africa in 1938. I learned about these ghosts of an unimaginable time in grade school. I loved that the world was so much larger and older than me, that there were mysteries to be discovered in my fleeting time on earth.

I love that feeling still. That is why I travel to places like this. That is also why I will return- to feel small and amazed once again. Next time, I will add a visit to Sambaa Deh Falls Territorial Park, where ancient coral tumbles down the river from the falls.

I walked the trail between Alexandra and Louise Falls and back, reading every interpretive sign along the way. The signs tell the journey of young Dene people on a portage past the barriers of the Twin Falls.

When you reach Tucho, the elders of all clans in the region will gather to hold ceremonies, celebrate, and give thanks. Every elder there will be called upon to use special healing gifts. There will be many new stories to tell and legends to retell to educate the young.

Interpretive sign, Twin Falls Gorge trail.

The restored portage trail is well-maintained and used heavily by modern life, including beavers, black bears, and likely other furtive creatures. A sturdy spiral stairway safely transports hikers from the trail to an overlook at Louise Falls. I have no idea how First Peoples made this trek, but I do know they would be more fit, agile, and adept at cross-country navigation than most of us modern folk.

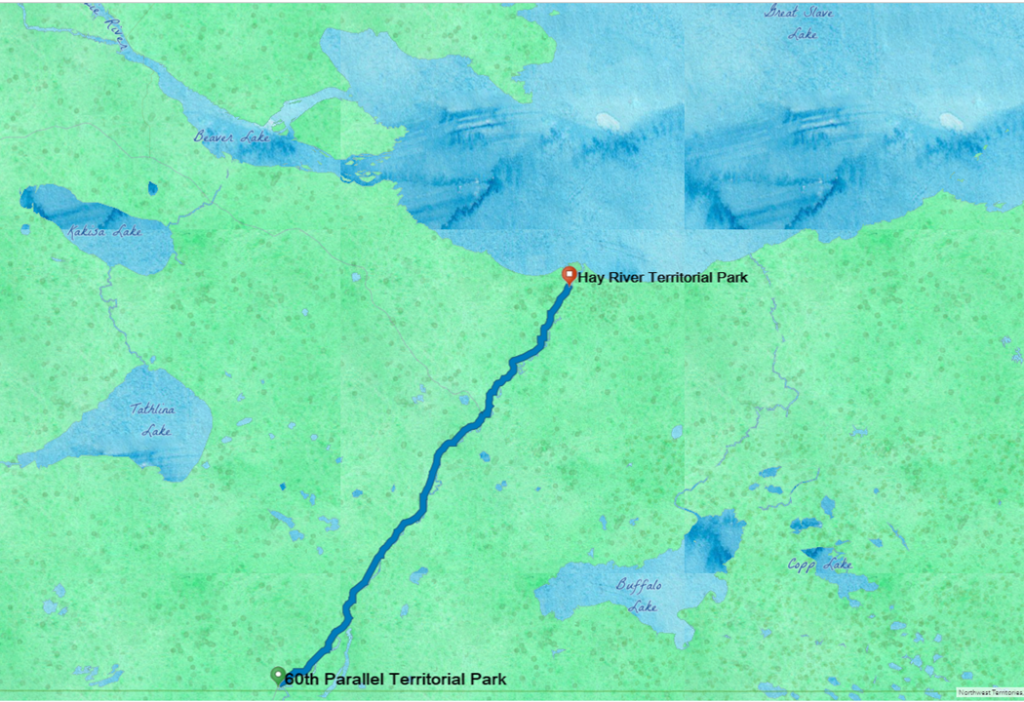

I had one last night to spend at Hay River Territorial Park. One late night to brave the sneaky foxes and creep down to the beach to try my hand at photographing the aurora. The Northern Lights were softer, greener, and the light show more brief. I was still entranced. I had spent the day becoming so small and insignificant. I could be one of those atoms in the sky, struck by charged particles from the sun, emitting light on humanity as I calmed.

For an easy, fun look at Deep Time, watch this PBS video.

References

Spectacular NWT- 19 reasons to see Great Slave Lake. https://spectacularnwt.com/story/19-reasons-to-see-great-slave-lake-now

What causes the aurora borealis, by EarthSky. https://earthsky.org/earth/what-causes-the-aurora-borealis-or-northern-lights

Twin Falls Gorge Territorial Park and Waterfall Routes. https://www.nwtparks.ca/explore/waterfalls-route