When you are a 4 day drive from home, it’s not a wise idea to become ill. I knew it was a possibility, and had really worried about the potential for decent medical care in a remote area. When I woke up sick on a Sunday morning, I knew I would need to get help that day. The bacterial infection that started with a tick bite in June was back with a vengeance. I sat feverish and in pain in a dark tent Googling medical care services by the glaring light of my cell phone. On a Sunday, my only option was Hay River Emergency.

I lay back waiting for dawn and wondering what would happen if they could not help me. Would I need to leave my car behind and take an emergency flight home? I felt foolish- why hadn’t I ditched my plans? Why didn’t I just stay home and hunker down? I thought of the coworker who sustained a strained back muscle just as her husband and kids left for a 2 week vacation in Glacier National Park. She stayed home in a dark house, miserable, to recover.

I need not have worried. The hospital was bright, up to date, and the staff friendly and professional. The doctor was as befuddled by my own when I showed him the lab results on the bacterium. They had not posted the sensitivity, so he did some research and guessed. They gave me antibiotic in the hospital and a prescription for more.

The bill came to $275 USD, which I could easily pay out of pocket. Most copays in the U.S. would be higher. I felt guilty as I watched a dark-skinned woman strolling and smoking outside, a bag and dripline peeking from under her jacket. She would have health care, I thought, but any extra expense would be a burden.

I needed to take it easy while the antibiotic kicked in, so I decided to drive to Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary. The sanctuary is a few hours’ travel toward Yellowknife, but scenic and lonely. It is best to fuel before going. I filled after crossing the Mackenzie River and paid dearly for it, more than I would at Hay River.

The day turned to sun as I drove. I crossed the Deh Cho Bridge, spanning 1.1 km across the Mackenzie River. The bridge is a technically challenging and expensive infrastructure solution. The bridge project struggled through redesign, a bankrupt contractor, cost overruns for materials, and weather. Finally it opened in 2012, replacing a summer ferry and winter ice roads as a way across the Deh Cho River.

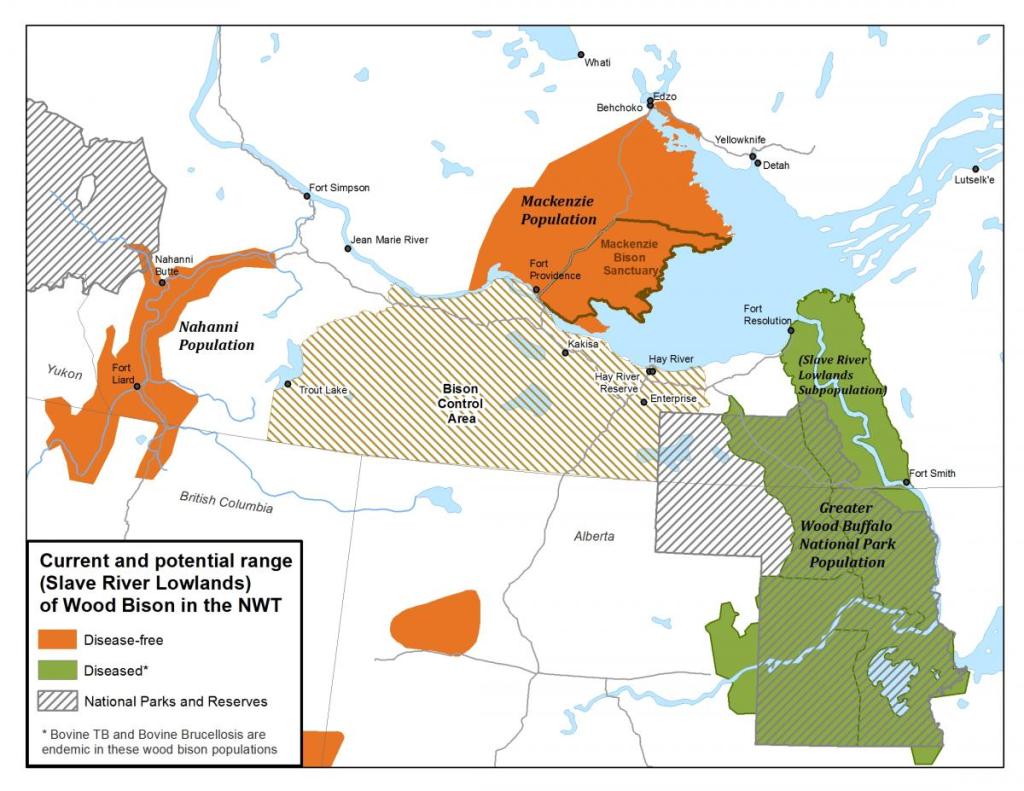

The river is a natural barrier for bison, and must remain that way to protect them, as you will see. This was apparently an unappealing idea to the bison during the bridge construction project.

Bison grates prevent the animals from walking onto the bridge on either side. They can’t be prevented from swimming, and bison managers have observed bison tip-toeing across grates in the past. If nature and man-made barriers fail, there is always the high powered rifle.

After the last Ice Age ended, about 11,700 years ago, bison had spread across habitable parts of North America. Bison evolved rapidly along with a changing climate. Ancient steppe bison gave rise to our modern bison and ultimately faded away. Plains bison were far more numerous than wood bison, though accurate population numbers will never be known.

If you see wood buffalo today, you are seeing ghosts. While all bison were decimated by overhunting during the development of the railroad, wood bison may have been lost to interbreeding. A seminal decision by managers of long-gone Buffalo National Park resulted in the transport of 6,600 plains bison to Wood Buffalo National Park. The animals hybridized and the plains bison transferred diseases from cattle into the Wood Buffalo herds.

Here is author Jennifer Brower talking about the park in a 2008 trailer by Athabasca University Press. Her book, Lost Tracks: Buffalo National Park, 1909-1939, is available from AUP as a book and free PDF download.

An apparently miraculous discovery of 200 isolated animals in WBNP mid-century led wildlife managers to hope that “pure” wood bison could be saved. Of 200 animals, only 23 survived the trip out of WBNP to establish the Mackenzie herd. The travails of transport and an anthrax outbreak decimated the herd.

While some populations appear to be disease-free today, it is not clear whether they are genetically distinct enough to call “pure”.

The two bison bulls below are from Northwest Territories: the bison in the upper photo is from Mackenzie herd and the photo below shows a bull from Wood Buffalo National Park. Both have a forward thrust shoulder, abbreviated hair on their heads, and other features of wood bison.

But the bull on the top has indistinct pelage on its abdomen while the bull on bottom has more of a woolly “vest” and bare thermal window like plains bison. Both these bison were photographed within days of each other, so changing seasons doesn’t explain the difference.

Later I learned that the MacKenzie Sanctuary bison herds were subject to anthrax outbreaks in the same season that Wood Buffalo deaths hit the news. The animals tend to use the road verges to get away from insect-thick forests in the summer, and stricken animals died there. Wildlife officers were forced to burn the carcasses in the ditch to contain the spread to other animals.

Historic management practices may have muddied the genetic lines between woods and plains bison, but each has adaptations for different environments.

Biomechanics may explain differences between wood and plains bison better than DNA at this point. Both wood and plains bison have a pronounced hump that allows them to forage in snow for food. But wood bison may not reach the speeds that plains bison needed to achieve to outrun long-gone predators. A woollier abdomen may protect wood bison from scraping by twigs or bites in the insect-rich boreal forest, while the plains bison’s bare thermal window may be critical to managing body temperature during hot prairie summers.

I saw no sign of wood buffalo on the way north, but instead, vari-colored forest and muskeg spinning by beneath a bright sky. I turned around in late afternoon, and woodland ghosts appeared.

First a few bulls emerged from the trees, then cows and a calf or two. Looking across stunted trees, I saw animals resting away from the road. With no traffic, I could stop and examine them through binoculars. They looked different from plains bison, with more abbreviated bouffs and steeper humps set farther forward. Were they really different? Did it really matter?

North America’s First Peoples viewed family and community in a more fluid way than settlers. Family units were not identified only by father’s name. Family consisted of a long list of ancestors on both sides of the family presented with their unique stories as part of a person’s introduction. People could become part of a community if they contributed to that community.

Perhaps biological necessity fostered a more tolerant culture, perhaps. As smaller populations, they would need to maintain a fluid culture, welcoming outsiders to avoid inter-family reproduction.

From an indigenous perspective, a buffalo with combination of wood and plains bison genes is a buffalo. Even if the wood buffalo is an ecotype instead of a subspecies, it is a buffalo. But our endangered species laws carry Western European bias toward genetic purity, and a hybrid isn’t necessarily valued or protected. The more refined genetic analysis becomes, the more hair-splitting about genetic purity occurs.

I watched the wood buffalo move in a stately parade just like buffalo do, in a vastly different environment from their prairie cousins. Poplar and birch, tamarack and spruce- there was nothing like grassy plains here. Their massive brown bodies carried a heavy history slowly into the woods, disappearing like ghosts bearing infinite knowledge of earth and sorrow.

At Mackenzie, the raven lives with bison just as on the plains. These long-lived, intelligent birds have a place in story for peoples of the north. Their lustrous black color is a result of being tricked by either ducks or owls. They have medicine power and wisdom, but can get mad when fooled. I imagined they were looking at me quizzically, wondering why on earth I traveled this far with an uncertain health status. But really, they may have been sizing me up for handouts.

Nightfall offered another opportunity to try my hand at photographing the Northern lights. I felt better after downing a gallon of water and a couple of light meals. I ate soup for dinner and sat with a cup of cocoa and marshmallows at the picnic table at my site.

In the falling light, shadows flitted through the woods. Suddenly, a fox appeared across from me, standing on its hind legs with front paws on the table. It looked at me with a Picasso face: a face made of two triangles joined at the base above its eyes, with triangular ears and eyes.

Still staring intently at me, it dipped its nose into the marshmallows floating on my cocoa. I exclaimed in surprise, causing it to spring away from the table. A dab of marshmallow whitened its nose. It stood and slowly licked off the marshamallow on its nose for a moment. I thought it looked resentfully at me, but maybe I imagined that. It disappeared into the forest.

I crawled into the tent, leaving my shoes outside under the fly. I set my phone alarm for 11, then tried my best to sleep. I pondered just turning off the alarm and getting some rest, but I had come this far hoping to see the northern lights once again. I could sleep tomorrow if need be.

A rustle behind my head caught my attention. Then, a swift, light pounce and two paws landed on the tent and my head. I hollered and hit the tent wall.

I got up before the alarm, not rested, and went to pull my shoes on. I couldn’t find one shoe, so I shone a light across the site. The shoe lay on its side in the middle of the site.

Darn foxes.

Bundled in fleece and a parka, I walked to the beach in the dark and set up my gear. A group of people say by a fire nearby, and I could see the shadows of lone photographers on the dark beach.

I wasn’t very good at this the first time as I hadn’t anticipated the difficulty of focusing on manual wearing glasses that wanted to fog up. But the aurora worked with me, shimmering in green and purple and red. I experimented with shutter times, not sure of exposure, counting “one-one-thousand, two-one-thousand” under my breath.

Soft waves washed the shore. Fire snapped and cracked and murmuring voices floated from the dark forms huddled around the embers. The crisp air cooled my cheeks, unnaturally warmed by my body’s attempts to burn out the infection.

In the firelight, foxes skirted by, half watching for opportunity, a gap in surveillance. I heard a French accent say, “See, the foxes. They are here.” The photographer was walking past me in the dark. He waved at the lights, which had softened. “It is over,” he said. “The light show is done.”

A Japanese photographer I recognized from camp had just set up his tripod. He paused and looked at the sky over the lake.

I shrugged. “It’s still good practice,” I said. “The stars are out here. We never see them at home because of city lights.”

The Frenchman shrugged back and walked away with his gear.

After he left, the lights arced across the sky, reflected in the waters of the Great Slave Lake. The Japanese photographer and I stayed awhile. My photos displayed marginal focus over time, possibly due to fumbling with gloved hands in the dark.

Since the forecasts for weather and aurora were good for the next night, I pulled up stakes and walked back to my campsite, rewarded for having at least tried.

When I returned to my tent, I pulled my shoes off a noticed a wet spot on my sock. Puzzled, I shone a flashlight in my shoe. I found flattened fox poop in the heel. The fecal pancake left a brown stain on my shoe liner when I dumped it out away from the tent. I carefully removed my socks, turning the stained spot inside, cleaned my foot, and put on a fresh pair for the night.

The furred sprites had wreaked revenge on me. I was mad at them, but intrigued. Little mischievous magicians of the forest, they were still wild spirits despite obvious handouts. As I dropped off to sleep, I saw that face of triangles and diamond-sharp eyes staring at me over a cup of cocoa.

Darn foxes.

References

Bison Bellows: Plains and Wood Bison: What’s the Difference? National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/bison-bellows-2-25-16.htm

Genetic analyses of wild bison in Canada: implications for recovery and disease management. 2016, Journal of Mammalogy, Oxford University Press. https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article/97/6/1525/2628020

Northwest Territories Species at Risk (map of wood bison populations): https://www.nwtspeciesatrisk.ca/species/wood-bison

Lost Tracks, Bower, Jennifer. Athabasca University Press, 2008, available online.

Thank you, Monica! Very well written and informative.

LikeLike