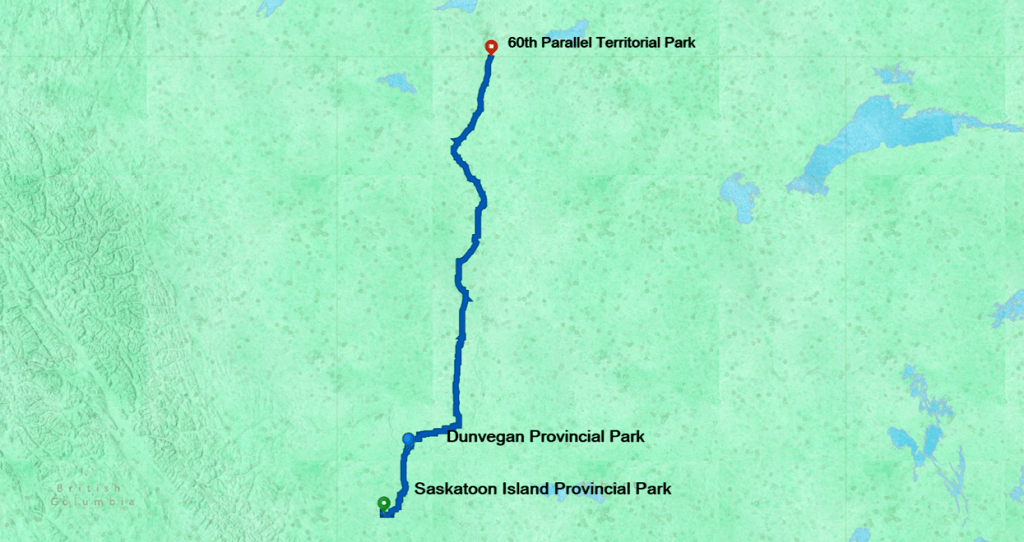

The world is made up of people who live to plan trips, and those who do not. I belong to the planners. I spend off-seasons charting routes on maps, researching places to stay, unearthing unique experiences, reading about wildlife and landscapes. There really is not an off-season, just in-between.

But the best part of travel is what we never plan. Surprises. Changes in perspective. Little gifts wrapped up with big bows.

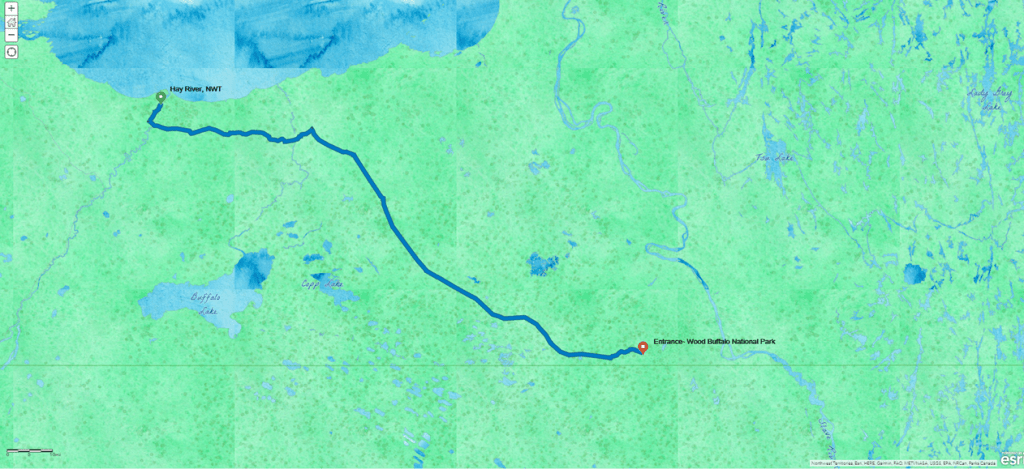

I reached Wood Buffalo National Park, the second largest national park in the world, only a week after I left home. This was the “trigger destination”- the reason for charting a road trip in the first place. By the time I reached it, I had so many unanticipated moments I might as well have been an astronaut wandering the moon. All those moments were created by water, some that flowed in ancient times, some flowing today.

I traveled to the second largest national park in the world to see its namesake, the wood bison. This park is a World Heritage site for those bison, a dramatic landscape, and the last stand of an endangered species. Water is the creator and the life of this place.

Lands shaped by water

Water shaped much of North America for hundreds of millions of years. Whether liquid or ice, water left traces you can find across many different landscapes today. Beneath the surface, water still shapes some lands with unexpected and sometimes sudden results.

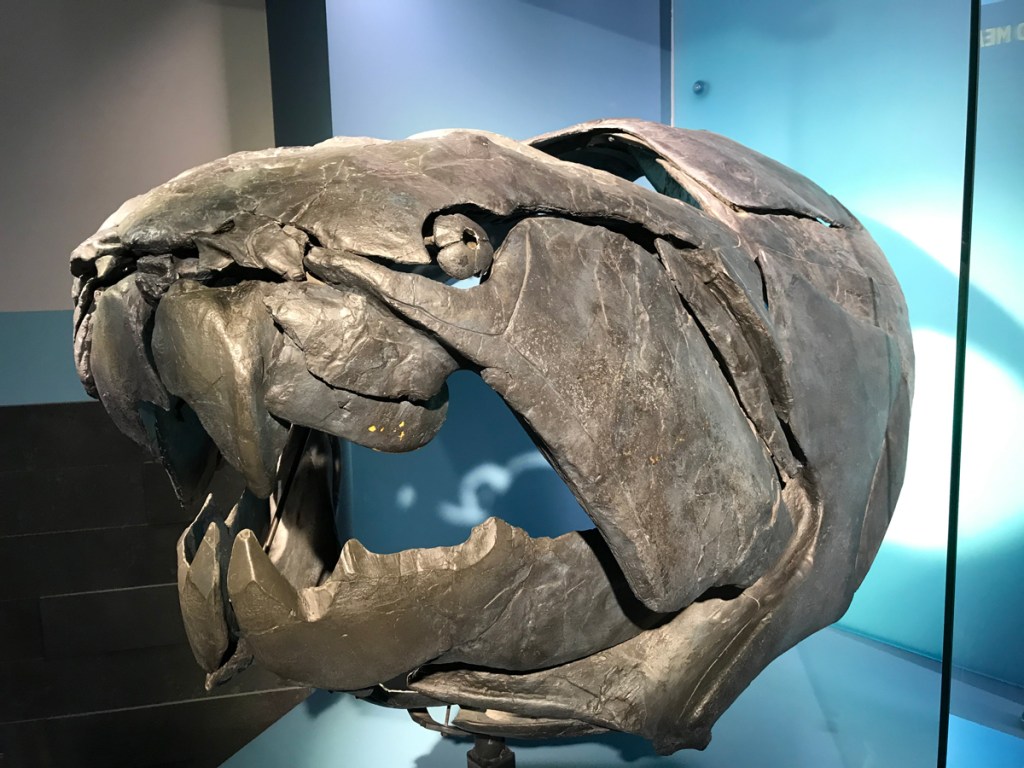

Laurentia, or the North American Craton, is a chunk of earth’s crust that has been around in one form or another for billions of years. As it crashed into other chunks of crust traveling from South Pole toward the north, Laurentia was pushed downward and covered with ancient seas. Seaways alternated with ice sheets to cover the land with water in one form or another.

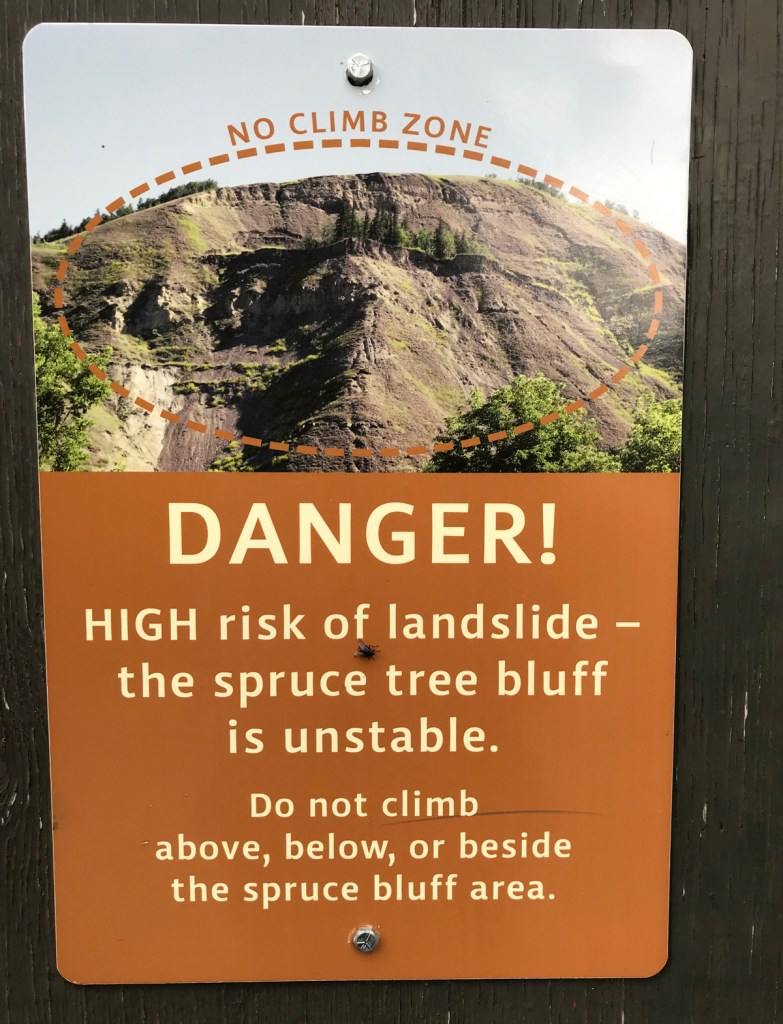

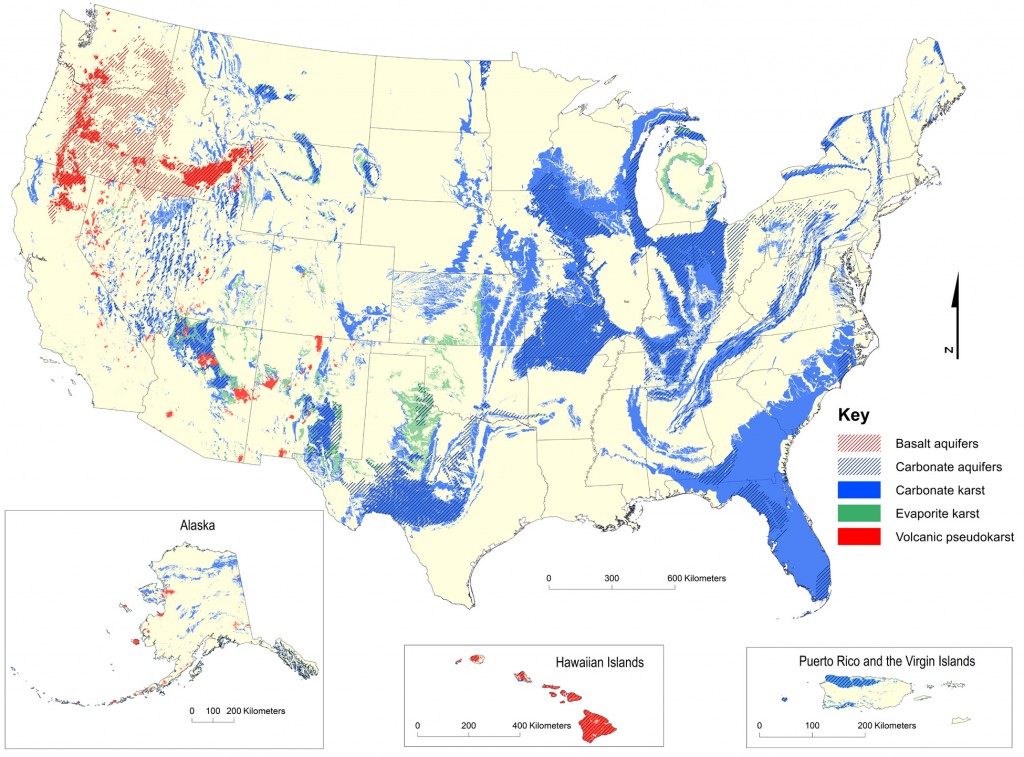

This watery history left its mark. Wood Buffalo National Park features karst topography, composed of gypsum, limestone, and dolomite: soft rock dissolved by water and sculpted into sinkholes, caves, hidden holes waiting to swallow the living.

Visual poetry describes karst landscapes. Cave flowers are not plants. There are cave blisters, hanging blades, half-blind valleys. Karst window, karst valley, cockpit karst, cone karst, syngenetic karst. This three-dimensional mosaic requires a montage of visual terms.

Karst landscapes hold that most precious resource for life: water. About 25% of the United States is karst landscape, and 20% of groundwater comes from karst reserves. People around the world depend on the fresh water running through undergound seams and pockets.

A karst landscape is dotted with water features. Pine Lake, where I stayed in Wood Buffalo National Park, is a uvula lake, comprised of multiple sinkholes that converged.

Karst landscapes are continually being reshaped. Surface and groundwater dissolves soluble rocks- limestone, gypsum, dolomite. The ground doesn’t dissolve in a planar fashion and just shrink like a collapsed souffle. Water worms its way through cracks underground, forming complex water systems. The Maligne River flows underground for 16 kilometers before it resurfaces in a canyon of the same name in Jasper National Park.

Karst features can form suddenly- and catastrophically. Collapse sinkholes can do just that, as the unsupported roof of an underground cave falls in. A sinkhole swallowed part of a house and sleeping resident in Florida. Libby Gunn, author of Thebacha Trails, describes the saga of a local resident whose dog suddenly disappeared into a 45-foot deep hole hidden under moss on the Rainbow Lakes trail in Wood Buffalo.

Hiking the trails in Wood Buffalo NP, I quickly found myself more afraid of the landscape than any animal. While the lure of caves may attract some, they are largely uncharted and very dangerous, according to Parks Canada cave expert Greg Horne.

I found that good ankle support was important hiking the Karstland Trail, and wished I had taken my heavier boots when I got inspired to hike the whole Salt Pan Lake/Meadows loop in one day. My ankles are pretty flexible after years of heavy use and injuries, but they were frankly sore in low hiking shoes that are usually just fine.

Salt Plains

Ancient waters left life today a gift when they vanished about 270 million years ago. A vast North American seaway slowly evaporated, concentrating saline water in pools as it disappeared. Specialized plants live in the salt plains, painting them with color.

The salt from this ancient sea attracts life today- including people. The first peoples to live in North America harvested this salt. Commercial interests took over during the fur trade era. Today, the Salt Plains now attract wildlife and travelers who readily remove their shoes to roam barefoot across the surface.

The area looks almost moon-like in places, with rocks covering the white surface. The salt eats at them, pitting some in almost coral patterns.

Walking across the Salt Plains, you will wonder how things came to be what they are- was that hole once a cloven hoofprint? Or did a rock dissolve away? Or spirit away? This is a magical place to let your imagination wander.

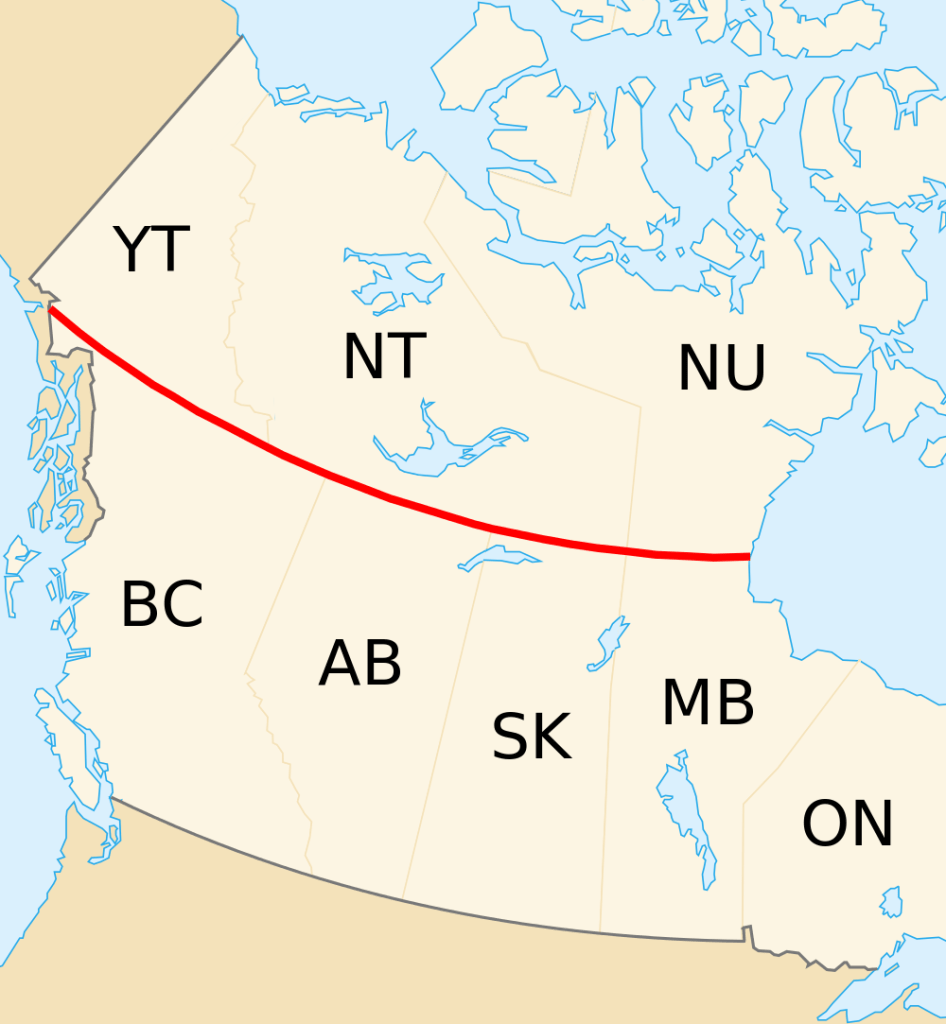

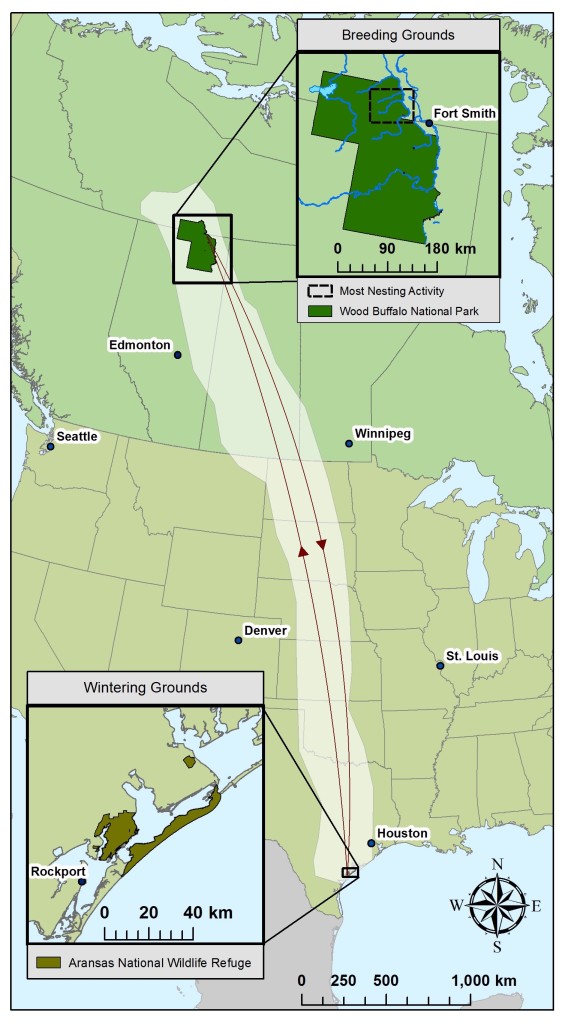

Whooping Cranes

Whooping cranes contribute another element of World Heritage designation for Wood Buffalo National Park. The complex of wetlands provide the last natural nesting site for wild whooping cranes. These majestic cranes, which stand 4-5 feet tall, migrate from Aransas, Texas to wetlands in the Wood Buffalo area, where they can safely raise their young before flying south for the winter.

The whooping crane remains critically endangered, and could easily disappear forever. Never a huge population, there were an estimated 10,000 whooping cranes flying over North America when European settlers arrived. Hunting, agriculture, and other human activities reduced the population to 60 by 1976.

At that time, ornithologist George Archibald took a fresh and innovative approach to captive breeding of endangered cranes: he became a crane “husband”. Challenges didn’t end there: saving the first viable egg and resulting chick, named Gee Whiz, took heroic effort. Watch George talk about the pioneering work that changed whooping crane conservation efforts, courtesy of the International Crane Foundation:

In partnership with the U.S. government, ICF’s work has helped the whooping crane recover to about 826 birds today. The future of these birds is not guaranteed: they are threatened by impacts to their breeding grounds from hydroelectric projects in the Peace-Athabasca delta, illegal shootings, sea level rise, and predation from bobcats flourishing after humans decimated the Florida panther and red wolf.

When you drive through Fort Smith, do visit the Northern Life Museum. Never a weeper, I teared up when I entered, only to be greeted by Canus, an iconic whooping crane survivor. Canus was rescued in an unprecedented international effort in 1964.

Canus was sighted during aerial surveys at Wood Buffalo with an injured wing and embedded piece of charred wood, likely the result of hitting a burnt tree during flight practice. He was captured and brought to Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. Despite a few more rounds of bad luck, Canus lived to 39 and became the sire/grandsire of 186 chicks.

After Canus’ passing, his stuffed body was returned to his birthplace. He now greets visitors in a whooping crane display at the Northern Life Museum and Cultural Centre in Fort Smith. Where he brings tears to the eyes of people like me, who never want to see our natural heritage disappear.

Wood Buffalo

I will talk more about the beleaguered Wood Buffalo in other posts, and I’ve added their history to this Story Map. This iconic animal, the namesake of the National Park and World Heritage site, was the reason for my travel and will be the reason I return again (pandemic allowing).

I’ll close this chapter with a video from Pierre-Emmanuel Chaillon, a brilliant photographer and videographer, and resident of Fort Smith. Mr. Chaillon notes that drone footage was acquired under a permit from Wood Buffalo National Park. More of Chaillon’s superb work can be found at http://www.pierreemmanuelchaillon.com/ .

References

A Glossary of Karst Terminology, compiled by Watson H. Monroe for the United States Department of Interior, 1899. https://pubs.usgs.gov/wsp/1899k/report.pdf

What is karst? And why is it important? https://karstwaters.org/educational-resources/what-is-karst-and-why-is-it-important/

A ‘Honking Big Cave in Canada’ Lures Geologist to its Mouth- New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/08/science/canada-cave-british-columbia.html

Cave explorer takes stock of hidden holes in Wood Buffalo National Park, Northern Journal, March 31, 2014.

End of an Era-Our Deepest Gratitude to the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, International Crane Foundation, March 2, 2018 https://www.savingcranes.org/end-of-an-era-our-deepest-gratitude-to-the-patuxent-wildlife-research-center/

Melinaguene [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)%5D

Ansgar Walk [CC BY-SA 2.5 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.5)%5D

Salt Plains Lookout, Wood Buffalo National Park, © J. McKinnon https://www.flickr.com/photos/iucnweb/9552353373/in/photostream/