I drove solo to Death Valley National Park one year and spent the whole trip looking over my shoulder. I committed no crime more serious than extremely distracted driving and hiking in a rich visual landscape of surreal abstraction and surprise. I would pull over or wander off trail for unnatural colors, unusual textures, or just a small shrub full of butterflies sitting in the middle of a barren.

And once, passing a coworker and friend on the way into the women’s room, she asked,”Hey, do you want to go on a kayak trip in Tonga?”

“Sure, sounds cool, sign me up,” I replied. “Where’s Tonga?”

That’s my temperament, orientation, and wiring: wandering, curious, focused on nature, taking in the world through my eyes. I think I hailed from nomads, following food across the landscape. It is not the best fit for today’s linear, boundary-defined, man-made world. But it is natural for me to be attracted to grasslands, where I can wander and find little surprises everywhere.

For most, this scene disappoints: no towering mountains or trees, no sparkling azure lakes, no man-made stuff. For people like me, it’s an invitation to explore. What’s more, I have permission from the ranger, who says that Grasslands National Park allows people to roam everywhere. Hilltops welcome after dinner strolls from camps, and tempt you from a track.

And navigation is not challenging here, even without a device. The land is heavily sculpted by water, with a distinct orientation and flow, and landmarks easily visible from the ridge tops. On Broken Hills Interpretive Trail, the yellow trail markers guide hikers down a path, but you can roam without fear of wandering up in the wrong drainage, as can happen in my area. Perfect.

One of my challenges hiking Broken Hills was catching up to prairie butterflies. They are really petite and speedy. This makes sense if you think about what they face: drying sun, a lot of wind, and no shelter from any airborne insect eaters. Wing size needs to be large enough to absorb heat and fly, but limited to avoid moisture loss and predation. At least that’s my amateur butterfly scientist hypothesis.

At any rate, I know that some butterfly flowers like ridge tops, and they attract butterflies. This happens in Eastern Washington, and sure enough, it works in southern Canada, too.

I also know the dark side of butterflies, as we humans interpret them. We poeticize them as flying stained-glass angels alighting on nectar-filled flowers. But they need protein, too, and will find it in carnivore poop, blood, rotting meat, and so on. Grasslands has its coyotes, as you can tell from night time howling and occasional deposits. I never find butterflies on the furry scat, but they will land on more moist scat.

Larger animals and birds frequent these areas. Wolves and bears that roamed the land were extirpated by settlers who couldn’t imagine coexistence with predators. But smaller herbivores are stalked today by coyotes that spread across North America with human settlers. Wary, they give hikers a chance to leave, then bound gracefully away.

An herbivore that doesn’t need to fear coyotes-and can injure feckless or ignorant humans-is the mighty bison. I’ve personally seen one stand off a pack of wolves in Yellowstone National Park despite a clearly broken leg. After awhile, the wolves gave up and ambushed an elk.

You can find traces of buffalo throughout the prairie landscape, including poop, laydown areas, and tracks dried in once muddy areas. As a prairie detective, you can take notes on where they sleep and what paths they use.

This buffalo bull at Grasslands appears unconcerned about either the weather or people.

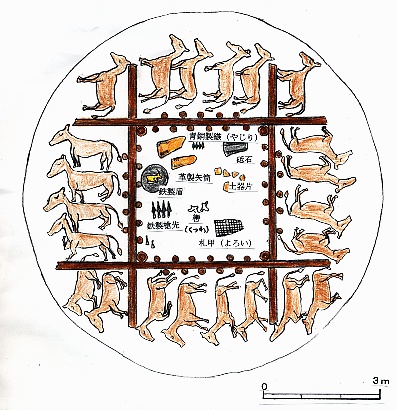

People have long wandered these lands; Parks Canada literature says the park includes 12,000 known tipi rings, and drive lines that people used to direct bison (or perhaps antelope) into traps.

I’m not a good enough prairie detective to determine whether piles of bones are a result of natural death or hunting, or how old they are. This is a harsh environment that can fatally tax young and old animals.

The bone at lower right looks really lacy and weathered, and many appeared cracked. I could make up a whole pile of stories about these, but really, they could even hail from the previous use of the area for ranching. Note that I moved nothing, and just took pictures.

If it doesn’t work out for an animal (or you), there are always patrolling vultures to clean up the aftermath.

Other random finds on my Broken Hills investigation include a shed antler and various flowers.

Like people long ago, I become nomadic in grasslands. Unlike those resilient, skilled people, I am not dependent on the landscape and its inhabitants. I’m just a prairie detective, with ancient genes directing me to root around for suprises hidden in the grass.

So now, 15 years after we left the show ring for a peaceful life at home, I needed to braid again. This time, there would be no biting, no matter how long it took. But first, I needed to wash the mud and blackberry canes from his tail, one terrible reminder of the struggle he went through alone. As I looked at him, I decided I would wash whatever I could reach, especially his bruised face.

So now, 15 years after we left the show ring for a peaceful life at home, I needed to braid again. This time, there would be no biting, no matter how long it took. But first, I needed to wash the mud and blackberry canes from his tail, one terrible reminder of the struggle he went through alone. As I looked at him, I decided I would wash whatever I could reach, especially his bruised face.

Then I wandered onto American Prairie Reserve, where the future vision is as expansive as the prairie horizon. APR envisions a 3-million acre fabric of private/public lands for bison, other wildlife, and people to roam free. The bison were boss in the unit I visited. There were no bison jams. I could wander across grasslands on all-encompassing treasure hunts to see rocks, fossils, and flowers. The skies were big, uncrowded. I found peace.

Then I wandered onto American Prairie Reserve, where the future vision is as expansive as the prairie horizon. APR envisions a 3-million acre fabric of private/public lands for bison, other wildlife, and people to roam free. The bison were boss in the unit I visited. There were no bison jams. I could wander across grasslands on all-encompassing treasure hunts to see rocks, fossils, and flowers. The skies were big, uncrowded. I found peace.

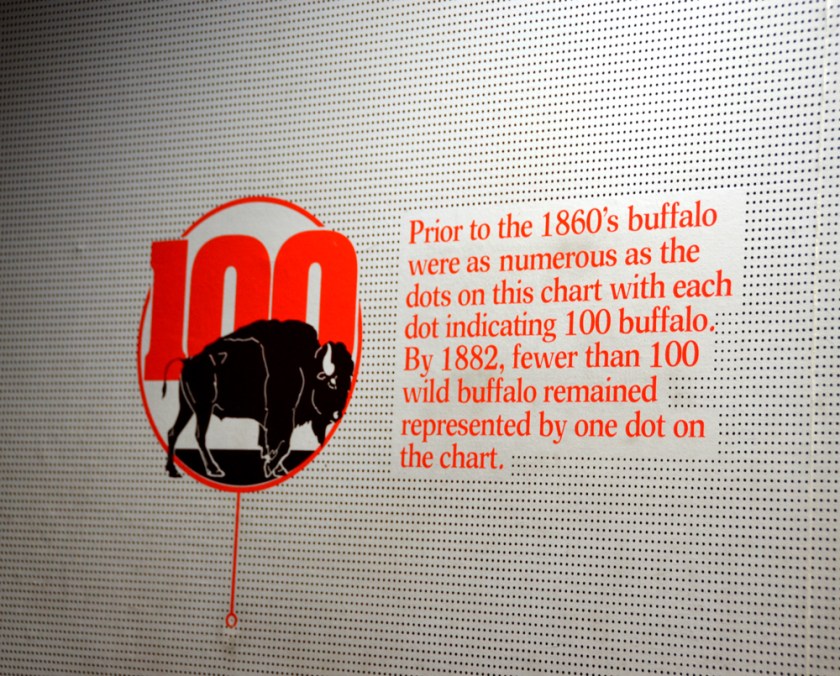

Bison may not need people, but we still need wild bison and wild places. We need them to remind us there are healthier, more viable alternatives to an urban life dominated by the technology explosion. We’re careening blindly toward a future of self-driving cars, artificial intelligence, and chat bots managing us via social media. We need to remember we’re not that far from our roots, that we are still governed by nature. We need bison to teach us some history lessons so we don’t repeat the worst of the past. We need them to school us in patience and give us peace.

Bison may not need people, but we still need wild bison and wild places. We need them to remind us there are healthier, more viable alternatives to an urban life dominated by the technology explosion. We’re careening blindly toward a future of self-driving cars, artificial intelligence, and chat bots managing us via social media. We need to remember we’re not that far from our roots, that we are still governed by nature. We need bison to teach us some history lessons so we don’t repeat the worst of the past. We need them to school us in patience and give us peace.

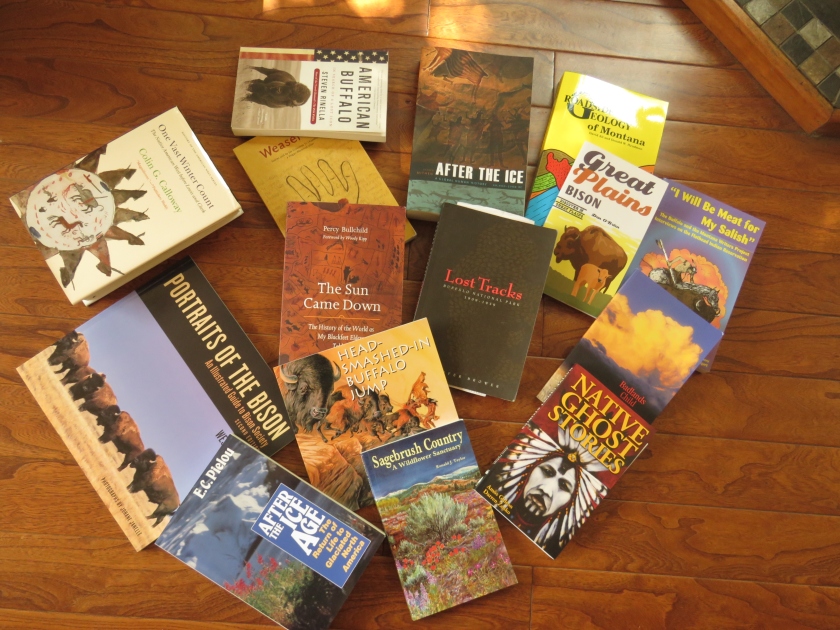

Plains Indian tribes followed these animals across North America, leaving their own trail, including camps, kill sites, and ritual locations. My first visit to a buffalo jump led to places where I could understand communal hunting, from Madison Buffalo Jump to the superb Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. This World Heritage site is the best preserved in the world with a phenomenal interpretive center.

Plains Indian tribes followed these animals across North America, leaving their own trail, including camps, kill sites, and ritual locations. My first visit to a buffalo jump led to places where I could understand communal hunting, from Madison Buffalo Jump to the superb Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump. This World Heritage site is the best preserved in the world with a phenomenal interpretive center.

Remember when you first felt freedom? Whether freedom is frightening or thrilling, people usually have a “first freedom” story. We realized we get to make choices about our lives, vote, leave on a plane by ourselves for the first time, walk through the door on our own apartment or house.

Remember when you first felt freedom? Whether freedom is frightening or thrilling, people usually have a “first freedom” story. We realized we get to make choices about our lives, vote, leave on a plane by ourselves for the first time, walk through the door on our own apartment or house.

Somehow I missed that stage in adulthood where people decide camping is too hard, and either stay in motels or travel in trailers with a compact semblance of home. I hit motels on long driving days, or when I need a shower and a real meal.

Somehow I missed that stage in adulthood where people decide camping is too hard, and either stay in motels or travel in trailers with a compact semblance of home. I hit motels on long driving days, or when I need a shower and a real meal.

Disasters aren’t disasters without images of people’s damaged belongings. After a flood, our screens scroll images of drowned livestock, crushed barns, mangled cars, crumpled roads and bridges. Earthquakes shear highways and splinter houses into junk piles with people trapped underneath. The awful feeling wouldn’t be there without us; it would just be an event.

Disasters aren’t disasters without images of people’s damaged belongings. After a flood, our screens scroll images of drowned livestock, crushed barns, mangled cars, crumpled roads and bridges. Earthquakes shear highways and splinter houses into junk piles with people trapped underneath. The awful feeling wouldn’t be there without us; it would just be an event. The speeding automobile smears the landscape into a monotonous panorama stretching for hours. We grow stiff from sitting and it seems endless. But speed did not create this impression of the prairie. Even settlers who rumbled along in wagons or on foot didn’t see the complexity of the landscape. There seem to be more books about hard life than prairie songs on the shelves.

The speeding automobile smears the landscape into a monotonous panorama stretching for hours. We grow stiff from sitting and it seems endless. But speed did not create this impression of the prairie. Even settlers who rumbled along in wagons or on foot didn’t see the complexity of the landscape. There seem to be more books about hard life than prairie songs on the shelves. Innocence is the culprit, aided by fear. Powered by animal or fuel, we travel the prairie as if in a foreign land. It looks different from our homes. The sky looms larger, with a hundred-mile view of circling weather and no hint what it means to us. Cacti lurk on the ground and rattlesnakes in the sage. The prairie has a different rhythm that enchants the curious or unnerves the timid.

Innocence is the culprit, aided by fear. Powered by animal or fuel, we travel the prairie as if in a foreign land. It looks different from our homes. The sky looms larger, with a hundred-mile view of circling weather and no hint what it means to us. Cacti lurk on the ground and rattlesnakes in the sage. The prairie has a different rhythm that enchants the curious or unnerves the timid. Each journey to dry country fills my eyes with the richness of seemingly barren land. This trip is my first as an artist to

Each journey to dry country fills my eyes with the richness of seemingly barren land. This trip is my first as an artist to

My car also displayed the damage of regular life.

My car also displayed the damage of regular life.

In the end, he wished me a good vacation and I continued my journey to Buffalo Camp. I set up my tent and sat down for dinner, watching the sun set over rich barrens ripe for exploration.

In the end, he wished me a good vacation and I continued my journey to Buffalo Camp. I set up my tent and sat down for dinner, watching the sun set over rich barrens ripe for exploration.

The 350 or so bison at this

The 350 or so bison at this

The

The